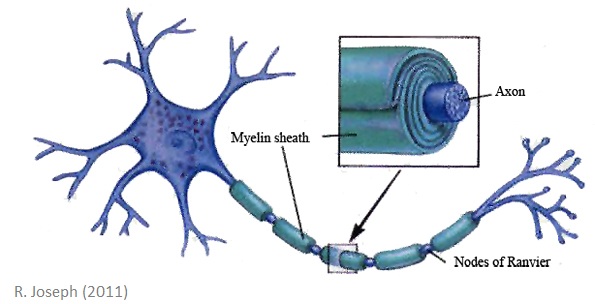

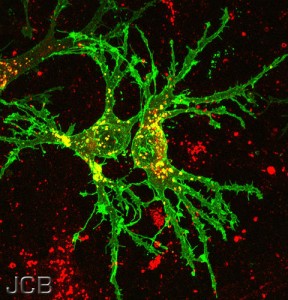

Any tennis player knows that the use of repetition is fundamental in tennis practice, and my last post How to Build a Tennis Brain explains why repetition works. Repeated firing of a skill circuit in your brain builds myelin, which improves the speed, capacity, and reliability of the circuit controlling the skill, and this improves our performance of the skill.

Great, but what does this mean for your practice? It means we can design our practice to exploit this mechanism and achieve accelerated improvement.

How can we practice better?

Geoff Colvin (Talent Is Overrated: What Really Separates World Class Performers From Everybody Else) used observations from researchers on the practice regimes of wide ranging experts, to develop a framework for what constitutes the most effective practice. The most important features of this “perfect practice” or “deliberate practice” are summarised below, and fit extremely well with the skill-building myelin mechanism we learnt previously (How to Build a Tennis Brain).

1. Practice activities are designed to achieve very specific goals

Top performers identify sharply defined elements of performance to improve, to ensure stimulation of a narrower range of circuits a greater number of times. They apply this concept to large complex skills by working on small specific parts of the skill. “Play” and non-directed practice do not target any particular skill circuits with the necessary focus, and represent lower quality practice. Note however, that play is essential in younger years when enjoyment should be the primary concern [Benjamin Bloom].

2. Activities are chosen at the edge of current abilities

Top athletes are continually attempting skills that are beyond their comfort zone. Practicing what you can already do won’t improve anything. Practice is designed this way so that small failures can be embraced and corrected. The most powerful learning stems from failure and correction over and over.

Daniel Coyle’s study of talent hotbeds (particular schools, academies, and clubs that produce a disproportionately high number of world class athletes) characterised great practice as follows: Try, fail, stop, think. Try again, get a bit better or a bit further, fail, stop, think (analyse errors), repeat.

Coyle likens this process to ice-climbing, where crucially the person is seeking out the slippery slopes, purposely operating at the very edge of their abilities, so that they WILL screw up. This is the key to accelerated improvement. By contrast, effortless, comfortable practice is a poor way to learn.

3. Repetition

Now that we know why repetition works, how is it best implemented? Coyle found that the training academies producing the best performers used the following strategy to achieve deep practice, which enables repetition to be more effective.

Chunking.This involves dividing a skill up into small fragments or chunks, resulting in smaller and less complex skills that can be learned and perfected individually. Using this method the student becomes intimately familiar with the components of each skill. These components or fragments of the skill can then be strung together into chunks of increasing size until eventually the complete skill has been constructed. Note that before chunking, students should get an impression of the whole skill (by watching it being performed and imitating), so that they can visualise the final goal.

Repetition. The foundation of practice, but more is not always better. More is better only if you are in a state of intense concentration. You must be: 1) at the edge of your abilities; and 2) still paying close attention to mistakes.

Feel it. Learn to feel the struggle that represents the edge of your abilities, the struggle of maintaining concentration and the feeling of striving for a specific goal, falling short, evaluating and trying again.

These steps are strongly embraced by the Spartak Tennis Club in Moscow, Russia. This club has only one tennis court, and a bare minimum of facilities, yet has used the principles above to create a quality of practice that is perhaps unrivalled. The proof is in their results. This one small club has produced Anna Kournikova, Marat Safin, Anastasia Myskina, Elena Dementieva, Dinara Safina, Mikhail Youzhny, and Dimitri Tursinov; and churned out more top twenty ranked women from 2005-2007 than the whole United States.

4. Continuous feedback is crucial

The performance of top players is carefully monitored for errors and ways to improve further. They take advantage of a range of feedback sources including coaching, self monitoring, competition results, and match statistics. The crucial role of your coaches is to keep you in the learning zone (near the limit of your skills) and to provide continual feedback. Experience allows them to assess where you are and the best route to your goal, and therefore what you should strive for next.

5. Mentally demanding levels of concentration

Deliberate practice must be difficult and draining. The difficulty comes from the intense concentration and close attention to errors that is required, and as noted above you should be operating close to the limit of your abilities. Practice without such concentration is unhelpful, and can even be detrimental to performance.

Not being highly attentive to errors can encourage flaws and poor technique to be developed, due to insulation or reinforcement of the wrong skill circuits. The best strategy therefore is to focus on shorter more regular sessions to ensure higher concentration levels during practice. This point is discussed in more detail in a previous post Optimal Duration of Practice for Tennis Players.

The methods described here build an ideal picture of what your practice sessions could be. While reading through this post you probably realised how far most “coaching” falls short of these ideals. The gap between typical coaching and the training described above, is where the power lies for you to shift your training to a new gear and make improvements quicker than others could imagine.

Please comment below with any of your own insights, or better yet share this post with any young tennis players you know (or their parents) (or their coaches)…

Thanks for reading.

Dave

My last post The Formula for Perfect Tennis Practice discussed the 5 key ingredients of world-class practice. My first reaction upon learning these key factors was to realise how inadequate my own practice was (or the activities that I used to call practice).

My last post The Formula for Perfect Tennis Practice discussed the 5 key ingredients of world-class practice. My first reaction upon learning these key factors was to realise how inadequate my own practice was (or the activities that I used to call practice).

One of the great break-throughs in studies of sports performance is the discovery that physical skills improve as a result of physical improvements in the wiring of our brain. This means we can physically re-wire our brain for tennis or any other sport.

One of the great break-throughs in studies of sports performance is the discovery that physical skills improve as a result of physical improvements in the wiring of our brain. This means we can physically re-wire our brain for tennis or any other sport.